BASICS: Steaks 101, Part One – Choosing the Meat

This is the first of a two-part post on one of the most popular foods for outdoor chefs. Grilling a great steak isn’t as easy as just flipping burgers or heating up some weenies for the kids. A great steak cookout takes some planning, some equipment, and a little knowledge of the bovine critter and how it gets cut up vis-à-vis how you like to eat it. How to COOK IT, as opposed to how to pick it out will be the next post.

This post will deal with the various types of steaks and their grading – in short, how to get off to a good start by selecting the best cut for your use, budget, and tastes. First, I’ll cover the most common steak cuts, their source, and their characteristics.

TYPES OF STEAKS

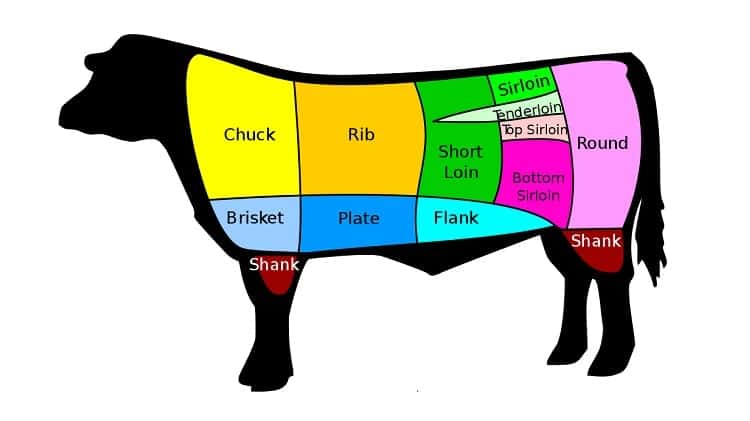

There’s an old saying that goes something like, “if you want the best meat, stay away from the feet”. That’s logical in some respects but what it actually translates to is avoiding the parts of the critter that handle locomotion. The front quarter consists of the chuck, brisket and shank – all “walking muscles” that get a lot of use and, thus, are relatively tough. Remember, we’re talking STEAKS for GRILLING here. Brisket and chuck, properly cooked are wonderful but they’d be awful if you tried to carve off a chunk and grill it. They need roasting, braising, and/or slow smoking to bring out the best of their flavors and textures. You can get chuck “steaks” at some stores but these are best used for braising like in Swiss Steak or Country Style (stewed in gravy) Steak.

The back quarter of the beef is similar to the front in terms of “grillability” and is usually called the “round”. Steaks cut here are flavorful but not very well fatted and are best braised, manually tenderized into “cube steak” or slow cooked. Round roasts can be cooked medium or medium rare but then need to be sliced very thinly across the grain for tenderness. Again, not the best territory for steaks, but there are folks who grill top round and say it’s good (I respectfully disagree).

Amidships, we find our subject cuts for grilling. There’ll still be a significant variation in tenderness but there are ways to deal with that. Here, in the portions most often called rib, plate, flank, loin, sirloin, and tenderloin are the best potential slices for cooking over the fire.

There are some geographic differences among types and styles of beef butchering. For instance, a Riibeye steak is sometimes called a Delmonico in certain parts of the U.S.A. and in some areas part of the tenderloin may be marketed as a Chateaubriand instead of cut into filets. In this discourse, I’ll try to use the most popular names and terms.

Here are the most popular steaks for grilling:

T-Bones and Porterhouses

With a bone that roughly resembles a “T” shape, these steaks come from the loin section and can be both flavorful and expensive. A Porterhouse is a T-Bone with a relatively large cut of tenderloin on one side of the bone (the larger side is the Strip Steak if deboned). It is up to the butcher to make the call on where the T-Bone stops and the Porterhouse starts but you’ll typically pay more for a Porterhouse pound for pound no matter what.

In choosing one of these steaks look for good marbling (streaks of fat in the meat – more about this later) and at least some fat left untrimmed around the edges and not cut away. Generally, the smaller the bone the higher quality the cut – larger boned pieces may cost less, though.

The larger “Strip” side of the steak will be the tougher of the two meat sections but in good grades will still be quite acceptable for knife and fork eating. The tenderloin side or “filet” is the tenderest but may not have as much beefy flavor. Put the two sides together, though, and you’ve got a considerable steak experience! I always like to eat a T-Bone or Porterhouse at home instead of in a restaurant because, when I’m through with my knife and fork I can pick up the bone and gnaw on it – some of the best tasting meat is right next to that bone!

Ribeyes and Clubs

These are variations on the same theme. They come from underneath the ribs and are known for good flavor, good tenderness and a modicum of fat content (helps with flavor). If the bone (part of a rib) is left on, it’s called a Club in some parts of the country. In others, it’s called a bone-on Ribeye.

If you buy a rib roast you’re getting a long section of this delicious meat. Cut the ribs away and you have Prime Rib which I consider a slice of roast and not a steak (although it is served like one).

Ribeyes tend to be a favorite steak of folks who aren’t averse to seeing and even tasting some fat on a steak. There are fatty strips in a Ribeye that contain great flavor by themselves and that also impart extra juiciness and flavor to the steak.

Strips

These are cut from along that T-bone in the loin discussed earlier. Usually, they are oblong and may have a little fat on one side. Sometimes there will be a line of gristle on one side but it is easily cut away.

Strips are typically moderately tender with excellent beefy flavor and good meat density. Often, people who don’t like Ribeyes because of their fat streaks will do well with a Strip because all of the fat (and usually there isn’t much in modern cuts) will be in one place, highly visible.

Sometimes you’ll see these titled as “New York Strips” or more simply “New York Steaks”.

Filets

These tenderloin cuts are the tenderest meat on the critter and are typically the most expensive cut at the meat counter as a result. They are small in diameter and are often cut thicker to make a more sizeable steak although thinner ones can be delicious on sandwiches and as breakfast steaks.

Folks who are very averse to fat on their steaks often choose the Filet because of its visible leanness. That lack of fat can create a cooking problem, though. Steaks need moisture from fat (both internal and external) to remain juicy and to provide something to drip onto the coals for flavor when grilled. That’s why you’ll often see filets wrapped with a slice of bacon.

As to flavor, I think Filets are okay but not the greatest. From good grade beef they’ll be succulent enough not to need marinating, certainly, but there are other cuts with more “beef” to them. Filet fans love the tenderness and often describe the flavor and texture as “buttery”.

Sirloins

My favorite steak in the whole wide world is a medium-thick Sirloin that hasn’t been trimmed too close and has a rim of fat about an eighth of an inch thick or so around the edges. These have to be special cut because the modern trend is to remove all the fat (sirloin fat is delicious!!!).

The Sirloin isn’t the tenderest steak by a long shot, but it does yield nicely to a knife and fork and has a fantastic beefsteak flavor found in no other cut. There are some variances in tenderness and appearance between the top and bottom sirloin areas but both are excellent for steaks (the bottom Sirloin may have some gristle depending on how cut).

Fortunately, you’ll usually find Sirloins priced significantly lower than the rib and loin cuts and that just adds to their great value proposition!

Flanks, Skirts, etc.

These cuts can be wonderful for grilling but are, essentially, working muscles and can come out tough if you don’t treat them properly. Study any recipe book and you’ll often see these cuts marinated then seared and sliced thinly for use in fajitas, salads, sandwiches, stir-fry cooks and the like. The flavor is meaty and great, but how you slice them makes a lot of difference.

GRADES OF BEEF

How a beef carcass actually gets graded is a very exact science that takes lots of different factors into account. Not all beef is USDA graded. There are not only general fat content sub-grades, but also relative aging and potential yield grades along with other measurements that weigh in. Complicated stuff.

For us meat customers, looking to get the best steak we can for the money we’re willing to spend for it, grading is much easier. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has four classifications of marbling (fat content of lean tissue) that we can generally discern or inquire about depending on how the meat market or department labels things:

Prime

Available from specialty meat markets and from Internet sellers specializing in expensive and very tender steaks and roasts, Prime beef is expensive stuff. It is so expensive, as a matter of fact, that most popular grocery chain meat sections don’t carry it or carry very small quantities. There isn’t enough demand for it.

The marbling (visible, tiny “veins” or streaks of fat in the lean parts of Prime) are either “abundant”, “moderately abundant” or “slightly abundant” but, nonetheless, it is gorgeous stuff. Even the tougher cuts of Prime, like the Sirloin, Round and Chuck will be mighty tender and the classically tender hunks like the tenderloin will be drop-dead “cut it with a fork” tender.

Flavor? Oh yeah – that entwined fat creates not only tenderness but also breaks down during the cook to yield a succulent result. This is great stuff! But, at a price. Just to have a couple of examples I priced USDA Prime Ribeyes and Sirloin. On a good day you’ll be paying well over $20 per pound!

Choice

This grade, still with decent marbling, used to be the mainstay of grocery butcher counters and still is for the more upscale stores. The marbling in a Choice cut sub-classifies into “moderate”, “modest”, and “small” but is still there and usually still highly visible. Choice steaks look good and are good. Honestly, if I can get Choice steaks that are not over trimmed (too much fat removed) I like them just as much as Prime and the cost is lower – running in the $15 per pound range at one Internet merchant I checked. You might be able to find a better price shopping sale flyers.

Select

This is the “workhorse” grade of grocery markets (no pun intended, yuk). The marbling will be slight but there will still be some, particularly in the better cuts like the loin and rib areas. Tenderness won’t approach Choice level and certainly not Prime, but it is usually at least acceptable, particularly if you know how to handle it during the cooking and any subsequent carving.

If you love beef and are willing to take some time to shop carefully for it, then cook it properly (next post will be on that subject) there’s nothing to be ashamed about serving Select grade.

Standard

“Traces” to essentially “no marbling” are the norms for Standard Grade beef. Much of this grade winds up either ground into hamburger or designated for special uses like canning or institutional kitchens where it is cooked down for soups, stews and mass food service. I have seen it offered for sale in the meat section of one big box store – it even looked tough!

Extreme Beef

You may have heard the term “wagyu”. This is a breed of cattle originated in Japan and prized for their predisposition to a high marbling percentage in the meat. An area name like Kobe or Mishima may appear in addition or along with the wagyu label. Prepare to take out a second mortgage for this stuff – Kobe Ribeyes sell for $60 per pound plus or minus a tad on the Internet. You can get free shipping if you shop around, though

Organic

I hate the term “organic” because it is so misused, but in buying beef it usually applies to a speciality type that has been range or grass fed as opposed to the more typical lot feeding for the finish. Usually, this beef isn’t subject to the USDA grading process because it is sold only via specialty butchers but you might find it graded if you look hard enough. Most often it is relatively lean and only lightly marbled if at all. To some (including me) it has a game-like flavor reminiscent of elk or buffalo. This isn’t always bad but I don’t find it as tasty as a well finished Choice selection. Prices tend to be similar to Choice, however. If your conscience demands some “health food” aspect to your steak or you eat lots and lots of beef as a constant menu item go for this.

Veal

Extremely popular in Europe, veal doesn’t get a lot of play in most of the USA and some consumer groups target it specifically for protest. Basically, veal is very young beef, usually a calf of less than 600 pounds that has been specially fed. At best the beef is humanely treated and butchered young and at worst veal calves are pent up, force-fed, and not allowed to move. Do your own research – this isn’t an editorial or a value judgment. I like veal and I’m no friend of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) but there’s a line there somewhere. Veal is tender and expensive for obvious reasons. I like older critters.

BEEF AGING

An interesting fact of life in the beef world is that letting it sit for a while after it is butchered actually adds to the flavor and savor of the product! It sounds counterintuitive, but it is really true – a steak fresh off the steer won’t taste as good as one that has been aged, even for a relatively short period.

There are two types of aging – wet and dry. Wet aging takes place, at least to some extent, for a lot of beef sold today. It occurs during the wrapping/packaging process and doesn’t result in any loss of beef weight or moisture. The natural chemicals and enzymes in the meat “break down” or flavorize/tenderize the meat as it waits for a period of days or weeks, typically. Occasionally wet aging may be done for longer periods under specially controlled conditions.

Dry aging is done only for the best grades of beef, most usually Prime. It won’t work on lesser grades because that marbling or fat graining talked about earlier is required for it to work. It also requires very precise temperature control and a precise humidity level. In dry aging the meat enzymes go to work to break down connective tissues and create a deep, rich, beefy flavor while they are tenderizing, too. Add some significant dollars to that already outrageous price of Prime beef for the aging process. It takes a while (time is money) and, typically, the meat is reduced in volume (weight) by about a third.

Dry aged beef is most often the bailiwick of high-dollar steakhouses. They have special coolers devoted to producing and maintaining an inventory of aged prime steaks. The chefs monitor the process and know how to cook it at just the right time. If you’ve ever had an aged Prime steak you’ll well remember the experience. The flavor is intense! Cost? Well, make sure you’ve got lots of cash or headroom on your credit card if you go to one of these steakhouses.

CONCLUSIONS

What it boils down to when choosing steaks might be something like this:

Grade – How’s your bank account?

- Check your wallet and your ego. If both are fat, go for Prime.

- If you’re a little flush and want to impress, go for Choice.

- If you are price conscious, shop for good looking Select.

Cut – How much visible fat do you want and what size steak?

- If you or your guests aren’t averse to a little fat on the steak, go for Ribeyes or T-Bones or Porterhouses. These can be BIG steaks! Porterhouses are often served huge and intended to be shared.

- A fat appearance compromise that works well is a Strip. Lots of lean, pretty meat.

- Sirloins are super flavorful but only moderately tender. But oh, that flavor!

- Filets are super tender and expensive and have no visible fat band. Often, they are small but thick.

Special Needs

- If you can afford wagyu, go for it and please invite me to your party. I’ll bring wine and promise to spring for the ten dollar stuff

- For thin slicing uses (stir-fry, salads, sandwiches, etc.) save some money by using flank steak, London Broil or another “belly” cut and keep it tender via the way you cook it and slice it.

- If you see a type of steak not covered here (and there are some) take the time to look it up to see where it came from. If it came from one of the tougher areas on the chart above, deal with it appropriately – it may not be suitable for grilling!

The next part of my “BASICS” series will be how to cook your selection. Anyone can grill a steak, but few can grill one perfectly.

BASICS: Steaks 101, Part Two, Steak Grilling for the Beginner – Some Good Basics

Part One of this post covered meat selection. In Part Two we’ll cover some proven ways to optimize the steak’s flavor, degree of doneness, and juiciness – how to COOK it.

One more meat attribute must be covered before we fire up the grill, however: THICKNESS

There is a fact of life in steak grilling: It is easier to cook a thick steak than a thin one!

The reason? Time. At any given grill temperature a thin steak is going to change temperature faster (cook) than a thick one and this translates to CONTROL for you. I think one inch is a minimum. An inch and a half is great.

Small, thin steaks are great for breakfast use or in sandwiches or to carve up on salads or for fajitas and such because you can cook them quickly. Results can be erratic but for rare and medium rare all it takes for a half inch steak at grilling temperatures is about a minute per side. Two minutes per side and you’re into the darker side of medium and often, well done. With a thick steak, you learn to cook by feel, not time or internal temperature. Read on for details . . .

PREPARATION

The steps described here are totally optional but are frequently used to both optimize and customize the outcome. If you don’t want to mess with these steps or are in a hurry, that’s okay. You can still do a great steak!

Rubs

A purist might say that a rub affects the flavor too much and overrides the natural savor. Maybe so. However, I think a light sprinkling of the proper rub can blend well with the meatiness and produce an excellent result. Just don’t overdo it.

The most common rub for steaks is a simple application of salt and pepper. Something similar is McCormick’s Montreal Steak Seasoning or similar steak rubs. The contribution of flavors like salt, pepper, garlic and onion can add up well but they should not be the dominant factor. You want your steak to come out meaty with overtones of other flavors that compliment that effect.

Beware salt! Salt is a desiccant and will take moisture out of the part of the steak it touches. Thus, using a rub too high in salt and/or leaving a salty rub on for too long can produce a couple of unintended results. First, the outer layer of the steak can be emulsified by the salt and turn mushy. Second, sometimes the heat will turn this outer layer into a hard “jacket” that may not have a pleasant mouth feel and may actually have a flavor by itself that doesn’t compliment the steak. Best practice? If you use a rub, keep it light and don’t rub the steak more than 30 minutes before the cook.

Know your MSG, too. Monosodium Glutamate is a flavor enhancer and tenderizer made from a naturally occurring substance in concentration. “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” is the label for the throbbing temples experienced by some moo goo gai pan consumers. MSG in reasonable levels doesn’t bother most folks but be careful using it. Because it has a tendering effect on meat, it can contribute (with the salt) to the unintended results described above.

Marinades

A marinade is a solution of flavoring agents that a steak “soaks” in for a period of time prior to the cooking. For some cuts, a reasonable marinade can add interesting dimensions and even help tenderize. However, as with rubs, I think they should be used with care.

There are lots of commercial marinades available. Most have a central or major flavor to impart (e.g. teriyaki or garlic) but some are more general purpose. Actually, it is easy to make your own marinade with just a few ingredients that are typically found in most home kitchens (see below).

Fact: The longer you leave a steak in a marinade, the more of the marinade flavor will be absorbed by it. As a rule of thumb and best practice I recommend a standard marinade time of about two hours for most cuts. Also, marinating should be done in the refrigerator, not at room temperature in order to further control absorption.

One gallon plastic food bags make wonderful marinating tools. Get the ones that seal well. They’ll hold one big steak or a couple of smaller ones easily.

Here’s a simple, basic marinade that nicely compliments the flavor of a good steak. Feel free to experiment with other and more ingredients. The quantities shown will be just right for a gallon bag.

Hub’s Basic Marinade:

Very lightly salt and pepper the steak or apply a very light coat of McCormick Montreal Steak Seasoning to both sides and the edges of the meat. Place the steak in the food bag.

Add the following liquid ingredients:

- ¼ Cup Worcestershire Sauce

- ¼ Cup Extra Virgin Olive Oil

- ¼ Cup Dry Red Wine (Merlot, Shiraz, Pinot Noir, etc.)

Note: It is okay to “eyeball” the amounts. They are approximate.

Slosh the liquid around and over the steak to mix it together and thoroughly coat the steak. Place in refrigerator for one hour. Turn bag over and continue to soak for an additional hour. Discard the liquid after use.

You can easily add more things to this if you want. I frequently add minced garlic.

FIRING UP THE GRILL

For steaks, we need to “grill” meaning cooking over relatively high heat and allowing the fats and juices from the steak to drop onto a radiant surface to flash caramelize and “sizzle” in order to impart that famous grilled flavor we know and love.

High heat will impart some aspect of “searing” to the meat as well. The BASIC NEED is to have heat high enough to cook the outside of the steak rather quickly without burning it and to accomplish a cook that does not dry the steak out even if it is to be cooked medium-well to well done.

Different types of grills do different things and this isn’t the place to argue what is best. Fact: You can do a wonderful steak on an inexpensive gas, charcoal, wood-fired and even some electric grills if you apply yourself.

I have found by experience that a grate temperature of 500 to 600 degrees is excellent for grilling steaks. Hood and cover thermometers are sort of relative devices and should be considered as “indicative” of overall heat level and useful devices for plugging the hole the manufacturer drilled for them (hood ornaments, my friend Billy calls them). For grilling steak, it’s the temperature at the grid or grate that does the work, not the temp “under the hood”.

Regardless of grill type, if you put your palm right over the grates and can leave it there for longer than two seconds it isn’t hot enough. That’s not very scientific, but it works. If you had an infrared reading thermometer it would show 500 degrees or more using this phenomenon of human skin. Most grills will take a while to get up to grilling temperatures – give them time. A friend of mine once had the habit of coming home from work, “flipping on” his gas grill to high heat, grabbing steaks out of the refrigerator, throwing them on then going about his business until he began to see smoke coming out. Then he’d flip them and cook for “a few more minutes”. He always wondered why his steaks didn’t have much flavor and varied a lot in terms of how done they were. Duh!

The grates themselves will usually get hot enough to impart grill marks or sear marks. These are pretty but don’t contribute to flavor. If you don’t get at least a little bit of grill marking, though, your grill isn’t hot enough. The grates should also be scraped clear of prior cooking debris before firing up and wiped with a bit of oil (peanut oil or Weber grill spray work well) to inhibit sticking. Also, believe it or not, a really hot grid will heat sear its mark and “let go” fairly quickly whereas a medium heated one may hang on to the meat for a long time resulting in your need to “tear it off” to flip it.

LET’S COOK

Okay, the steaks have optionally been rubbed and/or marinated. The grill is fired up and hot enough you can’t hold your hand over it for the length of any meaningful arithmetical exercises. Now, the steaks go on at refrigerator temperature – forty something degrees. Why?

It’s that time and thickness equation again. Not only is it easier to cook at THICK steak, it is easier to cook a COOL steak. Both of these attributes give you precious time and added CONTROL. This is especially true if you’re seeking rare, medium-rare or even well modulated medium steaks with perfect color and internal temperatures!

While you grill steaks pay attention! Do your imbibing of adult beverages after the cook. Don’t get distracted. The “life” of that expensive steak is in your hands!

The best steaks are “flipped” once, not over and over. Know your grill’s hot and cool spots and use them appropriately. TONGS are used to cook steaks, not forks. If you puncture the meat you’re leaving exit points for juices. Your own sense of touch is much more accurate and doesn’t poke holes in the meat.

JUDGING DONENESS – THE FINGER METHOD

It takes only a little practice, no equipment, and it works! Here goes:

The “Finger Method” involves actually touching the steak with the tip of your index finger and then comparing the feel of the steak’s surface with the feel of the flesh at the base of your thumb while making some non-obscene hand gestures. The steak will not burn your finger!

Rare . . .

Make the “OK” sign with your left hand, your index finger just touching, not pushing against your thumb. With your right index finger, feel the pad of skin right below your thumb. That’s the way a rare steak should feel to your touch. It will be spongy and not a whole lot firmer than a raw steak. You’re only cooking the outside third of it!

Medium Rare . . .

Do the same thing described above but apply heavy pressure between the thumb and index finger. The pad of skin below your thumb will still give easily, but will “tighten up”. That’s the way a medium-rare steak feels. You’re cooking this one about half-way through.

Medium . . .

Modify the “OK” sign by applying pressure to the tip of your right ring finger with the tip of your thumb. A medium steak feels like the pad of skin below your thumb. The goal here is a warm, pink center so, overall, the steak “gives” less to the touch.

Well Done . . .

Modify “OK” again and use your pinkie and thumb this time. The pad of skin below your thumb “hardens” just like a well done steak. You want it to get hot in the center but stay juicy.

With practice you’ll find you remember what each condition feels like without having to use your hand and the “OK” sign to imitate it. Just a quick touch with your finger to the top of the steak tells you the doneness! Just remember to do it, though – an overdone steak is overdone forever, whereas an underdone one can be cooked a bit longer.

Other notes on doneness:

If you absolutely must poke a hole and use a thermometer to get the internal temperature, here’s what to look for. Use a high quality, instant-read digital thermometer, not one of those analog dial things, they aren’t fast or accurate enough:

- Rare – very red, cool center – 125 degrees

- Medium-Rare – red, warm center – 135 degrees

- Medium – pink, warm center – 145 degrees

- Medium-Well – slightly pink, hot center – 155 degrees

- Well Done – gray, hot center but still juicy – 165 degrees

As a general rule, steaks will continue to cook when you take them off the grill. Thus, to do a great medium rare steak, it should come off just BEFORE it reaches temperature or feel, not after. This is a technique you’ll develop with time and experience. Don’t agonize over it. It’s like horseshoes, close is good enough.

A well done steak is not a “burned” steak and a rare steak is not a “raw” steak. Both degrees of doneness are legitimate and can be quite tasty depending on the meat. I’ve found that very tender steaks like the loin cuts, porterhouses and rib-eyes are best for rare and medium-rare cooking since they don’t need the cooking itself to break down tissue. On the other end of the spectrum, I think sirloins and strips are best medium because they tenderize a bit getting there. Try them and see what you think.

REST IT!

This is the last and one of the most important parts of cooking a great steak. Don’t take it off the grill and throw it on somebody’s plate! Set it aside for at least five minutes and, preferably, ten to let the juices redistribute and the overall temperature of the meat even out. This is yet another reason why you cook short of your target doneness level. In the “good ol’ summertime, ambient patio temperature won’t cool the steak significantly. In cooler weather you may want to lay a sheet of foil and a kitchen towel over it.

A steak that hasn’t been allowed to rest will “bleed” all over the plate regardless of doneness (well, unless you really overcooked the heck out of it – way past well done). Conversely, a properly rested steak will retain most of its juice (and flavor)!

RECAP – SEVEN RULES FOR GREAT STEAKS!

You’ve bought some great steaks (nice marbling) and you want to serve yourself and your guests great steaks (juicy, flavorful), so:

- Get thick ones – at least one inch, preferably an inch and a half.

- Rub and marinade at your discretion. If you don’t use rub or marinade, a mixture of 50/50 fresh ground pepper and kosher salt very lightly sprinkled over the steak before serving is a nice touch – but don’t use much. Let guests salt and pepper to their final taste.

- Wrap bacon around filets to provide “sizzle” fat (it won’t crisp so you may want to discard it after the cook).

- Allow time to get the grill VERY HOT. Most “ruined” steaks were cooked on a grill that wasn’t hot enough. A clean, lightly oiled grid helps, too.

- Cook from refrigerator to grill. A room-temperature steak gives you less time to control the cook.

- Learn and use the “Finger Method” to judge doneness. If you have to use a digital thermometer, don’t repeatedly poke the steaks! Never, never, never cut one open.

- Cook to just short of the doneness level you seek. Steaks routinely gain five degrees or more after they are off the grill.

- Rest the steak before serving it.

If you think all of this is complicated, you’re right! Cooking a great steak requires care and knowledge in the selection of the meat and some accumulated skill in using the grill to get the steak to proper doneness. Enjoy the learning experience and your “misteaks” if any!

EPILOG — A FEW MISCELLANEOUS NOTES AND COMMENTS FOR THE FUN OF IT

- Another great “topper” for steaks is steak butter. Lots of recipes exist for this but I take a stick of salted butter and let it come to room temperature (soften) then combine it with two cloves of minced garlic and one half teaspoon of brown mustard. Wrap it in Saran and refrigerate until it hardens. Put a couple of pats on a hot steak. Delicious!

- Alas, everyone has different tastes. I think steak sauce (e.g. A-1 or Heinz 57, etc.) are the ruination of a great steak or the salvation of a lousy steak depending on what is needed. Cook what you like. A friend of mine slathers everything he eats in ketchup so I just ignore him and try not to take it personally.

- Some grills and cookers allow either direct flame grilling or infra-red (very high temperature, close heat) cooking. Grate temperatures on these cookers can be a thousand degrees or more. They take time to get used to but can produce a great steak. Give yourself some experimentation and learning time if you have one of these.

- I often “reverse sear” steaks. If you have a smoker, “warm” the steak using smoke (temp 180 or less) for about 45 minutes before you grill it. This requires either a smoker and a grill or a smoker/grill like my Memphis Advantage which can do both (refrigerate steaks while the heat rises to grilling temperature). This adds a light and enjoyable smokiness that grilling alone does not impart.

- If you are using charcoal, a handful of wood chips on the fire (doesn’t take much) just before you put the steaks on the grids will give some nice added smokiness.

- Similar to the above you can wrap chips or pellets in foil and put them on the bars or lava rocks of a gas grill. This can be touchy, though. High dollar gassers have a chip “drawer” for this.

- You can get “add-on” metal grates that, in addition to producing somewhat spectacular sear marks, move the “sizzle” right up under the meat instead of down on the coals or diffuser. This really intensifies the grilled flavor. GrillGrates (grillgrate.com) are my favorite.

Last Updated on August 17, 2020 by Judith Fertig

Leave a Reply